Photo Credit: AQ’S Corner LLC

Artificial intelligence is already embedded in the systems schools rely on every day. It appears in writing tools, plagiarism detection software, behavior monitoring platforms, adaptive learning products, grading assistance tools, and administrative systems designed to improve efficiency. Policy and research organizations such as the Brookings Institution and the RAND Corporation have documented how these technologies are now routinely used across education and other public-sector systems, often advancing faster than the governance, oversight, and evaluation frameworks meant to manage their impact.

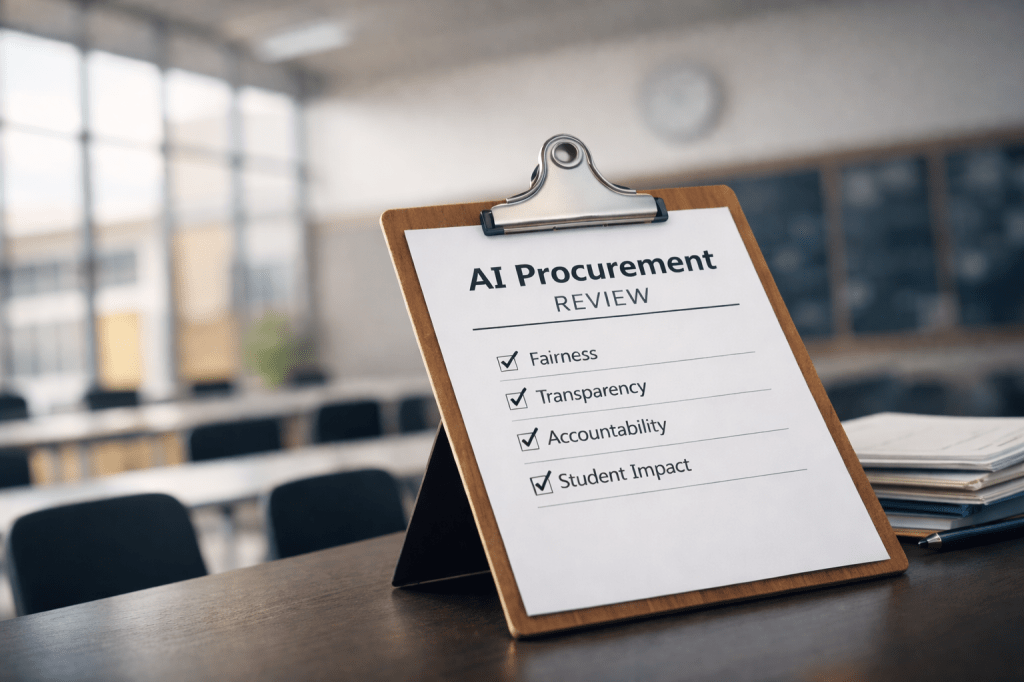

Much of the public conversation focuses on how these tools are used after they are deployed. Far less attention is paid to what happens before they are purchased, when critical decisions about data use, bias, accountability, and long-term impact are made.

From a technology risk and governance perspective, that gap matters.

Schools often adopt AI-powered software under pressure. Budgets are constrained. Staffing is limited. Vendors promise measurable improvements. Pilot programs move quickly, and contracts are signed before deeper questions surface about accuracy, fairness, transparency, and student impact.

At that point, schools are no longer evaluating a product. They are managing exposure.

This article is written for district leaders, administrators, and anyone responsible for approving technology that directly affects students and families. It is not an argument against educational technology. It is an argument for slowing down just enough to make informed, accountable decisions before AI systems are embedded into classrooms, workflows, and student records.

AI Bias Is Not Just a Technical Issue

AI bias is often framed as a technical flaw that engineers will eventually fix. In education, it is more accurately understood as a governance issue.

AI systems reflect the data they are trained on and the assumptions embedded in their design. When those systems rely on incomplete, unrepresentative, or historically biased data, the outputs reflect those same patterns. In school environments, this can surface as uneven flagging of student writing, misclassification of behavior, inaccurate assessments of engagement, or distorted performance signals.

For example, AI-powered grading or plagiarism detection tools can flag student work as suspicious or low quality without clear explanation, leaving educators and families to question outcomes after decisions have already been influenced.

Research from the RAND Corporation has documented how algorithmic systems can introduce bias and error when deployed without sufficient oversight and accountability. One widely cited analysis, The Risks of Bias and Errors in Artificial Intelligence, explains how these issues emerge when systems are adopted without strong governance structures.

When these systems operate in environments involving children, the consequences are not theoretical. They affect real students, real families, and real educational outcomes.

The question is not whether AI can be useful. The question is whether schools understand the risks they assume when these systems are adopted.

Questions Schools Should Ask Before Purchasing AI Tools

Before signing a contract, schools should be able to answer the following questions. When clear answers are unavailable, that uncertainty is not neutral. It is a signal.

1. How has the system been evaluated for bias and error?

Vendors should be able to explain whether their tools have been tested across diverse student populations and learning contexts and whether any independent evaluation has taken place. Internal testing alone is rarely sufficient. Evidence matters more than marketing claims. Districts seeking research-backed approaches can reference the EdTech Evidence Exchange, which promotes evidence-based evaluation of educational technology.

2. What data does the system rely on, and how is that data handled?

Schools should understand what data is used for training, what student inputs are collected, how metadata is generated, how long data is retained, and whether information is reused or shared. When minors are involved, transparency around data practices is essential. Guidance from the Common Sense Media highlights key considerations for AI tools and student data privacy, including how educational products collect and protect student information.

3. How are errors identified and corrected?

No AI system is flawless. What matters is whether educators and families have a documented process to question outputs, flag concerns, and receive meaningful responses. If there is no feedback or appeals pathway, errors can persist quietly and disproportionately affect certain students.

4. Who is accountable when harm occurs?

Responsibility may be shared between vendors and districts, but that responsibility should be clearly defined before deployment. Contract language matters. Governance does not end at rollout. It begins there.

Procurement Is a Policy Decision

AI adoption is often treated as a technical or instructional choice. In reality, procurement is a policy decision.

When a school district adopts AI-powered software, it establishes expectations about fairness, transparency, and accountability. Those decisions shape how technology influences educational experiences long after deployment.

Policy research from institutions such as the Brookings Institution has shown that technology decisions made without governance frameworks tend to reinforce existing inequities rather than reduce them. Schools do not need to become AI experts to make responsible decisions, but they do need documented questions, clear answers, and the willingness to pause when those answers are incomplete.

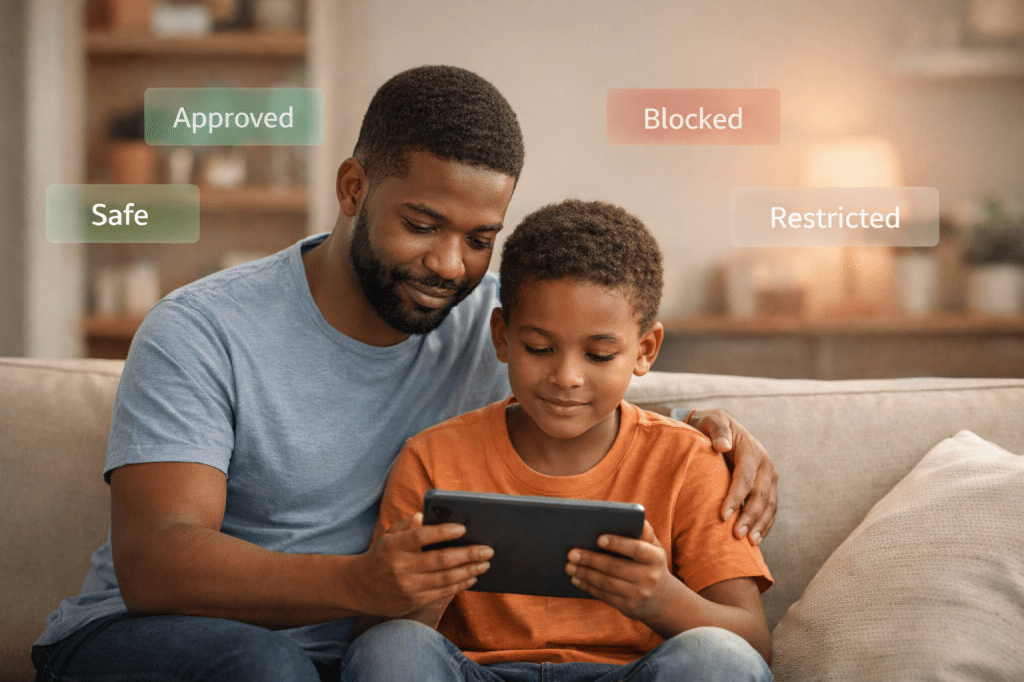

Why These Questions Matter for Families

Families are often the last to learn that AI systems are influencing their child’s education. When concerns arise, parents may not know who to contact or how decisions were made.

Clear pre-purchase evaluation creates a record of decision-making that schools can rely on when families ask how and why AI tools are being used. That transparency supports trust before issues escalate and becomes increasingly important as AI systems are embedded into assessment, discipline, and academic tracking processes.

Trust is not built during a crisis. It is built in the decisions made long before one occurs.

Moving Forward Without Fear or Hype

AI in education does not require panic. It requires care.

Schools that slow down long enough to ask better questions before purchasing AI tools are not resisting innovation. They are managing risk responsibly.

The goal is not perfect technology. The goal is informed decision-making.

When schools ask the right questions early, they protect students, support educators, and reduce long-term exposure. That is not hesitation. That is leadership.

Leave a comment